Core Composition and Function: The Core of 2014 Part 1

Written by Leo Shveyd, CSCS FMS

During the two-and-half decades that I have been involved in fitness, the definition of "the core" and consequently, core training has evolved. Part of the evolution is subjective (meaning I have learned more about the topic) and part is objective (as a profession there is more and better information about the subject area). With so many great minds in the rehab and fitness arena contributing daily in the information age, a good deal of terrific data exists about the "the core". In this article, I will attempt to define what makes-up the core, its functions and suggest an approach to core training.

I. Core Composition

My introduction to the core occurred in fourth grade during the Presidential Physical Fitness Test (PPFT). If memory serves me correctly, the test consisted of dead-hang body weight pull-ups, push-ups, a one-mile run for time, a bent knee sit-up test (with a partner holding your feet) for maximum repetitions in 60 seconds, etc. According to my fourth grade Physical Education teacher, the PPFT's sit-up portion tested the "abs" and this was my first introduction to a definition of the "core." With little guidance about the quality of the movement, and quantity being king, the goal was to do as many repetitions as possible with no regard for how each one was performed. What I didn't comprehend at the time was that each one of the activities in the PPFT tested the core.

Soon thereafter, the fitness industry professed that sit-ups were bad (but nobody ever explained why). Sit-ups were then substituted by crunches as core training supposedly evolved to a safer, more effective way to strengthen your core! One of my friends, who was a high level collegiate athlete, would literally do hundreds of crunches per day. If you saw this guy without his shirt, you would notice his "six pack" and assume he has a strong core, right? Not so fast my friend...this highly conditioned individual had such severe back pain that he had to give up his sport as he was preparing to try out for the US Olympic team. So what gives? How could someone who looks like Hercules, and have a "core" that appears as though it is made of steel, have back pain?

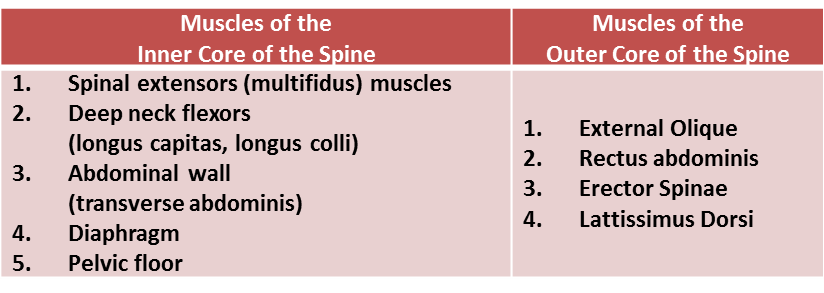

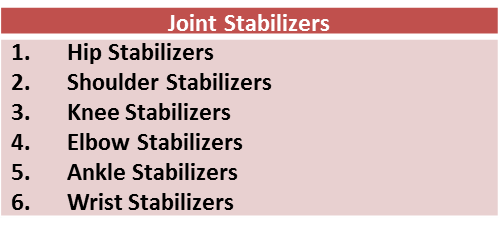

To answer this question, one must understand the composition of the core and its interplays with the entire body. The core consists of many parts and layers, initiating at the muscles that surround and protect the spine. Kyle Kiesel, citing Bergmark (4), hypothesized the presence of two muscle systems responsible for maintaining stability of the spine. The "global or superficial musc[ular] system" (outer core) consists of large torque producing muscles that act on the spine without directly attaching to it. These muscles provide general trunk stabilization without the capacity to control intersegmental motion. The "local or deep muscle system" (inner core) is made up of muscles that directly attach to the lumbar vertebra and are responsible for providing segmental stability and control.

In addition, I believe the core is also comprised of the stabilizer muscles of every joint of the extremities when under load. Categorizing muscles as stabilizers is tricky because the same muscle can be either a "stabilizer" or a "mover" depending on whether a joint is under load in a particular movement pattern. In my opinion, the sum of these parts (spine [inner and outer level]; plus the stabilizers of the hip, shoulder, elbow, ankle, wrist and out to the extremities when under load), collectively comprise the core. Below are the muscles of the core, broken down by segments of the body or the respective joints.

These parts that comprise the core are the foundation of posture, efficient movement and athletic performance. As the definition of core has evolved, so too has our understanding of its function and how to improve it.

II. Core Function

The functions of the core are respiration (breathing), continence, postural control, joint/segment stabilization, movement generation and energy transfer (Kiesel). In order to efficiently perform the most basic movements, in addition to high-level athletic feats, an individual must have a functioning inner core. The inner core must be in balance with the exterior muscles of the outer core of the spine. Moreover, the stabilizer muscles of any joint located on an extremity must counter-balance mover muscles (i.e. vastus medialis [knee stabilizer] and rectus femoris [prime mover]) of a given joint under load. This enables the core to be both mobile and stable in the appropriate segments through the entire system.

In  Mike Boyle's book, Advances in Functional Training and Gray Cook's book Movement both authors lay out a concept that originated from a conversation between the two: the joint-by-joint approach. In short, the joint-by-joint approach states that joints have a primary function, either mobility or stability, with each alternating joint trading functions. For example, the ankle joint is a mobile joint, the knee stable, the hip mobile, the lumbar stable, the thoracic mobile, the cervical stable. While the joints each have a primary responsibility (mobility or stability), should that joint be unable to function optimally, the joint above or below provides added support.

Mike Boyle's book, Advances in Functional Training and Gray Cook's book Movement both authors lay out a concept that originated from a conversation between the two: the joint-by-joint approach. In short, the joint-by-joint approach states that joints have a primary function, either mobility or stability, with each alternating joint trading functions. For example, the ankle joint is a mobile joint, the knee stable, the hip mobile, the lumbar stable, the thoracic mobile, the cervical stable. While the joints each have a primary responsibility (mobility or stability), should that joint be unable to function optimally, the joint above or below provides added support.

Take the thoracic spine, a mobile joint, as an example. When it becomes stiff, the body will provide mobility in the joint above (cervicals), below (lumbars) or both. This is one of the magical aspects of the human system. It is a survival mechanism, a short-term secondary solution, so-to-speak. These adjustments are a way to keep your body functioning until it has a chance to reboot, up regulating the primary system (mobility in thoracic spine), while down regulating the secondary system (excess mobility in the cervical and lumbar spine). Your core works much in the same way. When dysfunction occurs at different levels of the core, the body recruits nearby partners, whether joints, ligaments, tendons or muscles that weren't primarily designed for segmental stabilization, in order to assist with fortifying a particular region. This stability is artificial and a mere safety mechanism. For instance, when a person is incapable of diaphragmatic breathing, the inner core is not optimally activated. As a counter measure, the body will rely on the larger exterior muscles such as the hamstrings, for example, to stabilize the core.

While it is true the hamstrings have some postural responsibility, their primary role is hip extension and knee flexion. When asked to stabilize the core in addition to their primary role, they often fatigue and become prone to injuries. Said another way, asking the hamstring to play both roles is like asking a point guard to handle the ball and play center at the same time. It is not impossible to do, but hard for the average Joe's hamstring to thrive in that role. If my memory serves me correct, only the great Magic Johnson was able to do so successfully (play Center in the 1980 NBA Playoffs when Kareem Abdul-Jabbar got hurt). But I digress. Interestingly enough, most elite level athletes have unparalleled compensation pattern abilities. Many have the ability to use their secondary systems and do so successfully.

Breathing is the first thing we do when we enter this world. It goes without saying that breath is a prerequisite to life, as well as the foundation of core function and performance. Without proper breathing patterns, your inner core cannot optimally activate and sequence. By sequence, I mean the inner core of the trunk and the stabilizers must turn on before the outer core and prime movers, specifically with a precise level of activation. This centers your joints, providing postural support and stability at each engaged joint. In turn, the muscular system becomes the primary system of support for movement. When sequencing is inefficient, ligaments, tendons and joint structures must act as stabilizers and bear the brunt of segmental force transfer through the body. Therefore, proper breathing is the prerequisite that sequentially and efficiently activates the inner core of the spine. Therefore, proper breathing is the first function of the core!

Once this is properly activated, the job of the inner core is to stabilize and allow for segmented movement of the spine. Along with the inner core, the main responsibility of the outer core of the spine is to prevent flexion, extension and rotation according to Dr. Stuart McGill. Essentially, your trunk is made to stabilize, allowing you to transfer force from your limbs bottom-up or top down. This is the core's secondary function. In sum, the function of the core is first, respiration and second, controlling movement.

For example, when you watch a high level sprinter at top speed, you will see very little movement at the belly-button region, while her limbs propel her forward. Moreover, her joints are stable in the frontal (side-to-side) and rotational plane (i.e. little rotational movement at the knee). This principle applies to much of athletics, and life in general.

For example, when you watch a high level sprinter at top speed, you will see very little movement at the belly-button region, while her limbs propel her forward. Moreover, her joints are stable in the frontal (side-to-side) and rotational plane (i.e. little rotational movement at the knee). This principle applies to much of athletics, and life in general.

Therefore, training the core must focus on activation of the respiration mechanism and preventing flexion, extension and rotation of the spine. Dont miss part 2 of this article: Training the Core.

Related Resources

-

Movement Principle # 10

Posted by Gray Cook

-

Movement Principle # 5

Posted by Gray Cook

-

The Power of First Impressions

Posted by Brett Jones

Please login to leave a comment

6 Comments

-

helen 6/4/2015 5:17:48 PM

Dear Leo,

Thanks for all of the great information. I'm certified FMS and also Medical Yoga. There is often debate in the yoga community about when a student should be taught core stabilization or breathing exercises. In my Medical Yoga training we believe the core can and should be taught on day one. In the Iyengar school of yoga there is less emphasis on the core and breath for first year students. The focus is on strengthening the legs and proper alignment for stabilization of the spinal column. The Iyengar school believes the nervous system must be strong enough to handle more specific breathing practices like those required for core stabilization. Any thoughts? -

Brenda LaMont 6/4/2015 3:57:21 PM

Excellent article. Vast majority of people working out with poor movement and breathing patterns. Thanks for hammering home how and why breathing pattern is first!

Anyone know of video that demonstrates this concept so they can see it.They sure feel it when we train it! -

Sara Cory 6/4/2015 5:18:11 PM

Hi, great article and breakdown of the difference between inner and outer muscles, but I surprised to see no mention of either psoas or quadratus lumborum! As I have been educated these are at the heart of core stability. Psoas directly feeds down from the diaphragm, attaches to all of the lumbar vertebrae and sacrum, goes over the hip sockets and attaches to the femurs. Is it not the deepest core muscle?

-

Colleen Jones 12/18/2014 7:12:36 PM

Thanks for your article. My physio has been doing some deep visceral work on me to loosen up my diagphram, and your article helps me to understand why it's so important!

-

Peter Szymanski, PT, CFMT 6/4/2015 5:23:13 PM

Excellent article! The one thing I would add: The inner core also includes the deep fibers of the psoas muscle, and the deep fibers of the quadratus lumborum (used to be known as intertransverarri). These are intersegmental fibers that form a ring around each vertebral segment along with the deep multifidi. These are automatically activated when the spine is in efficient alignment, and with prolonged contractions.

Looking forward to part 2.

-

Hugh 6/4/2015 5:17:57 PM

Thank you Gray for confirming the philosophy that I have come to believe, that core control and joint stabilization are essential to functional strength and keys to maintaining or increasing the "functional bubble" as I like to call it. I started in the personal training world 10 plus years ago, where you only learn to train the global system for the most part, unless you get introduced to FMS. After 5 years of experience in the field of physical therapy and a compressive Pilates background, achieving that balance and syngery between both local and global has become my personal fitness strategy.