The benefits of using the FMS within USA Gymnastics

Written by Dave Tilley FMS

My name is Dave Tilley. I have my doctorate in Physical Therapy, recently became Board Certified in Sports Physical Therapy, and currently am studying to obtain my Certified Strength and Conditioning Specialist credentialing. I was a competitive gymnast for 18 years, which ended with spending 4 years on the Springfield College Men’s Team. I also have been coaching both Men’s and Women’s competitive gymnastics for 12 years, and currently still coach. Not surprisingly, given my background, I specialize in the rehabilitation and performance enhancement of gymnasts. I coach in the North Shore of Boston, and treat gymnastics clients at Champion PT and Performance in Waltham, MA.

I have been fortunate enough to work with a range of gymnasts, all the way from the youngest recreational athletes all the way up to collegiate and elite level athletes. Along side my clinical and coaching life, I also spend a large deal of time traveling the country to lecture on gymnastics topics through my company, SHIFT Movement Science and Gymnastics Education.

I took my first FMS and SFMA class right after graduating from PT school about 4 years ago, and then went on to take the next few levels of coursework. I have spent a lot of time with the system as one part of my practice, which gives me a unique perspective on its application to gymnastics. Having put hundreds of gymnasts through the FMS and SFMA, today I wanted to share with you some of my thoughts on why I feel it’s beneficial to use the FMS within the sport of gymnastics.

. @usagym athletes are doing functional movement screens under the watchful eyes of @greg_moore13 & Steph Young. pic.twitter.com/223fkohzjN

— St. V Sports Perform (@DefiningSports) September 30, 2015

Thoughts on The Patterns

1. Overhead Deep Squat

- Gymnastics is a jumping, landing, and squatting sport. I feel strongly that teaching and regularly screening for proper squatting/landing mechanics is one of the biggest things anyone can do to combat a variety of different injuries in gymnastics. The landing forces of gymnastics have been recorded in research to be between 7 – 17x body weight. Unfortunately, many gymnasts continue to demonstrate non optimal landing patterns, placing notable stress on their ankle/knee structures over time. Not to mention, the infamous “stuck” landing is much more obtainable when muscular squat dominated patterns are used to dissipate forces. Screening and improving this pattern as needed is crucial to longevity and performance in gymnastics.

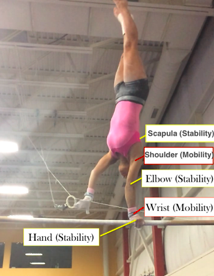

- If you think about it, during the overhead squat the gymnast has to statically control both arms and the upper body overhead in the presence of a dynamically changing condition of the lower torso and legs. That’s a mouth full for the gymnast keeping the arms in control while the body and legs move. In my mind that looks a lot like what might happen during uneven bar skills like giants, free hips, many other swinging skills. It also could be a puzzle piece to controlling handstand based skills, and overhead conditions like tumbling/yurchenkos (vault skill). All of these skills have different patterns and positions that are context specific as the body is fixed in this test vs not fixed during skill work. But, I can get behind the idea that this test puts a unique demand on the shoulders that may be applicable to gymnastics.

- The deep squat screens a pattern, not an isolated muscle or joint. Many gymnasts I have screened struggle with this test quite a bit. Although excessively stiff lats and calves are commonly found, there are many possible reasons why it is limited. It could also be a reflexive anterior core control issue, or a simple lack of awareness for squatting mechanics, which is equally as common. Many things about a gymnasts movement profile can be further investigated by starting with this pattern.

2. Hurdle Step

Before the countless hours of training that would help them become Olympic champions, the @USAGym team were screened pic.twitter.com/WlPux4Yh0K

— FMS (@FunctionalMvmt) August 10, 2016

-

Many people talk about how the hurdle step (along with other tests) can look

at reciprocal motion of the legs, which also happens quite a bit in gymnastics. Running for tumbling and vaulting require rapid force development in a short amount of distance for skills (vaulting, 3 steps before big tumbling passes). This pelvis dissociation also shows up in many tumbling, leaping, and inbar skills during swinging. It’s good to know the gymnast doesn’t have a huge problem with the basic motions or have a side to side asymmetry in this lower body motion before we start fancy running drills.

- A hurdle is a fundamental basic for both men’s and women’s gymnastics. It’s a key technical aspect to developing huge power for a tumbling pass or vault. From a very young age the gymnast uses their dominant leg for all of their hurdling, and also some women’s beam series like back handsprings. These basics also evolve into higher level tumbling passes that connect 1 ½ twists to step out motions. I think there’s value in making sure that an asymmetry doesn’t pop up to the point of a 1/3 or 2/3 hurdle possibly leading to a movement issue elsewhere.

- The hurdle step pattern also gives one opportunity to see how the gymnasts leg can perform in a single leg stance format. Again, you can’t blame one thing for it, but there are plenty of times for both men and women single leg stance with hip extension with superimposed balance is needed while the rest of the body is moving. Beam, floor non acro elements, running again, and more.

3. In Line Lunge

- Any women’s gymnastics coach should be in love with this test. Hello baseline balance beam screen.

- It’s super important to look at the connection of hip, knee, and ankle mechanics during triple flexion and it’s integrations with the trunk for skills. They go to this pattern a lot and many times the lack of control can create lots of issues both injury and performance wise.

- You’d be amazed to see how many of my gymnasts do poorly on this test because they defaulted to lower back extension with their lunging and can not maintain dowel contact along their spine. I think that speaks a lot to a gymnast who goes to lumbar motion as their main stabilization pattern. This is concerning for me as a medical provider and coach, in relation to a lack of active core control being compensated for by loading the static stabilizers of the spine (pars and ligaments primarily) to absorb huge forces during skills. Although there is lacking research to present a direct correlation, for this scenario may be a hint at spine overload, possible injury, and non optimal core performance.

- I’m definitely interested to see what a gymnast’s frontal plane function is for this type of motion in all planes. Single leg jumping/landing and asymmetrical jumping/landings happens all the time in gymnastics. We aim for a double leg landing that creates equal force dispersion, but due to the high variability in such complex skills this often does not occur. Due to this, having pristine single leg control is very important.

4. Shoulder Mobility

-

Here’s another one I’m a big fan of for gymnasts, especially in looking at their default strategy to use their upper extremity quadrants both overhead and reciprocally. I saw a surprising amount of 2/3 asymmetries in many of my gymnasts that needed correcting. I think one reason for this is for the gymnast having a dominant arm with pirouettes on bars, tumbling, round off entries on floor and vault, and other skills. I also think true soft tissue extensibility problems are very common, despite gymnast “looking flexible”. Many athletes I work with have excessive amounts of capsular hyper laxity, but still have true limited overhead motion when controlling spinal extension compensations. This is concerning for micro instability and other issues at the shoulder an hip. A quick shoulder mobility screen may catch something very important here.

Here’s another one I’m a big fan of for gymnasts, especially in looking at their default strategy to use their upper extremity quadrants both overhead and reciprocally. I saw a surprising amount of 2/3 asymmetries in many of my gymnasts that needed correcting. I think one reason for this is for the gymnast having a dominant arm with pirouettes on bars, tumbling, round off entries on floor and vault, and other skills. I also think true soft tissue extensibility problems are very common, despite gymnast “looking flexible”. Many athletes I work with have excessive amounts of capsular hyper laxity, but still have true limited overhead motion when controlling spinal extension compensations. This is concerning for micro instability and other issues at the shoulder an hip. A quick shoulder mobility screen may catch something very important here.

-

How the gymnast uses their thoracic spine matters a lot. If they have an issue from this related to mobility, control, or pattern driven, it’s important. It may mean they struggle to use their thoracic spine during skill work and may overload their lumbar spine. This is a big issue in gymnasts and this is just one of many ways to check it out in the FMS.

How the gymnast uses their thoracic spine matters a lot. If they have an issue from this related to mobility, control, or pattern driven, it’s important. It may mean they struggle to use their thoracic spine during skill work and may overload their lumbar spine. This is a big issue in gymnasts and this is just one of many ways to check it out in the FMS. - That 2/3 or 1/3 shoulder asymmetry is a big radar flag for me. Thinkabout what’s going on in the gymnasts system if they are bilaterally loading hundreds of high force handstands, tap swings, giants, high force tumbling, and vaults on an asymmetry? Or if a male gymnast is loading it with bilateral parallel bar swings, hundreds of pommel skills, or jams on high bar? The list can go on but I think there’s something to be said for picking up on and correcting these asymmetries early.

-

Shoulder Clearing Test – Many gymnasts are sneaky, try to betough,or simply may not realize their shoulder pain isn’t just a normal part of training. Shoulders, elbows, and wrists literally serve as a second pair of weight-bearing hips, knees, and ankles for gymnasts. For that reason, they take a lot of mileage and we need to be regularly checking in on them for pain. There are huge rates both instability based or more biomechanical rotator cuff / labral issues in male and female gymnastics.I think shoulders can get beat up in gymnasts on both sides of the spectrum. I thi

nk some get pain because they have huge localized imbalances and altered joint mechanics. I think others have too much motion everywhere they get instability and beat up their shoulders. I think some just have an issue putting all the pieces together for a pattern. For whatever reason, if they test positive for pain you better find someone to help get to the bottom of it before it sneaks back up to bite you on you down the road.

5. Active Straight Leg Raise

-

Step ins for hiccups on bars, toe ons/toe circles, some release moves, beamseries, and other skills are kind of hardcore active straight leg raises. There are plenty of other more typical active straight leg situations in gymnastics too related like the obvious leaping and split leaping for women, and I think scissor work for mens pommel horse also can go into this category to a degree. For all these reasons and more, this test has huge carry over to gymnastics.

Step ins for hiccups on bars, toe ons/toe circles, some release moves, beamseries, and other skills are kind of hardcore active straight leg raises. There are plenty of other more typical active straight leg situations in gymnastics too related like the obvious leaping and split leaping for women, and I think scissor work for mens pommel horse also can go into this category to a degree. For all these reasons and more, this test has huge carry over to gymnastics.

- Every gymnastics coach and gymnast in the world wants to have fantastic toe touches, pike positions, and perfect over splits on both legs. On the surface this may seem like a “how far can I get my leg over my head test”, but it’s much more. How the gymnast gets their leg there is really the focus. As I’ve said before, there are many more things to splits and pikes than your hamstring and hip flexibility. Knowing of mechanics of an active straight leg raise outside of how high can you get your leg and if soft tissue is tight is big. Like for example, can the gymnast reflexively fire their core and maintain good spine/down leg position in hip extension when they raise their leg for the pattern? To me that’s much more important. I have unfortunately dealt with too many cases of gymnast who have lumbo pelvic control and spinal positioning problems that show up as serious hip or hamstring growth plate injuries. Gymnastics culture automatically chases more flexibility, when in reality that is the last thing they need. This test, along with some other more gymnastics specific screens, can help uncover this motor control problem and save someone from a long road of spinning their wheels in the mobility department. I wonder if coaches and gymnasts would be surprised to hear that a quick active straight leg correction may quickly get them that equal split on both sides they’ve been dying for, without always needing more stretching.

6. Trunk Stability Push Up

- First off, as many people know the trunk stability push up isn’t a measure of arm strength. It purposefully changes the push up parameters, and then allows for a look into how well the gymnast can automatically create spine stability centrally before they use their extremities. Pretty important in my eyes. In the milliseconds gymnasts have to catch the low bar and nail a perfect release move to handstand, I think it’s more about turning the right things on, at the right time, and in good coordination rather than how many hollow rocks you did in the last month of conditioning. It’s also kind of funny to see the faces they make when they realize what the test is all about. There is a lot to be said about making sure gymnasts do not constantly live in a high threshold, high tension core strategy. They must equally train the low threshold and lower level motor control for injury prevention and optimal performance.

- Press Up Clearing Test –

- I can’t emphasize enough the importance of regularly screening a gymnast for lower back pain. I use a series of 7 back pain screens on every gymnast I work with, in an effort to impose a variety of different force demands on the back commonly seen in gymnastics. If a gymnast has pain with a simple prone press up test, that’s concerning. It could be a quick fix but it could be the start of something serious. Remember they load that motion hundreds of times per day under very high force and speed for beam, tumbling, yurchenkos, and tons of drills. Lower back pain and fractures are an epidemic in gymnastics. Along with pain or no pain although not specific to this test in the FMS, I think the quality and presence of hinge points into extension are very important as well. Although I don’t know if we can prevent them all, I think early screening like this and other pre-hab/smart training can go a long way to make a dent back pain rates for young gymnasts.

7. Rotary Stability

- The rotary stability test can again help bias the ‘soft’ or deep cores reflexive and automatic function while the trunk stability push up can give a better indication of the ‘hard’ or outer core. For me the improper balance of low threshold/ ‘soft’ core training compared to overload of high threshold/ ‘outer’ core use in gymnasts is huge. As pointed out, the importance of core control and low threshold spine stability can’t be over stressed.

- Along with a low / high threshold training imbalance, I think it’s extremely common for gymnasts miss training the core in a full 360 manner. In my experience it seems to be the anterior core is trained more than the posterior, which is trained more than the lateral and rotary core, which is trained more than proper intrinsic function related to breathing and the pelvic floor. I think this is one test that is good to both raise attention of both a coach and gymnast to possible issues related to this. I know I added in much more rotary and lateral core work once I saw that the rotary stability was across the board the biggest problem for my gymnastics team. Not to mention, gymnasts many times train a lot of active spinal rotation or sidebending motion for gymnastics skills, but sometimes overlook the “anti” rotation or sidebending that is crucial for athletic performance. For this reason, I program a ton of turkish get ups, bear crawls, and unilateral weighted carries for the gymnasts I coach.

- The rotary test has also been on my mind a lot in conjunction with rolling patterns for girls that show a lack of fundamental core control. Part of me thinks always going to the dominant side for round offing, twisting, release moves, one-armed skills, and more would throw off the system into a central asymmetry. Again, I have been surprised in the last year to see some notable asymmetrical rolling pattern issues and 2/3’s on rotary stability for my gymnasts. I haven’t quite gotten to the bottom of it, but again, I think this is something worth knowing about for a gymnast.

- Spine Rock Back Clearing Test

-

A gymnast should have the capability to fully flex their lower back without painor limitations. I’ve found it very common to see gymnasts who live in extension chronically show poor breathing patterns, and lose unweighted spine flexion. Living in constant lumbar extension puts stress on certain aspects of the spine as well as may set someone up for fulcrum based dynamic microinstabiltiy of the hip in extremes range of motion. Also, I have had 2 gymnastics patients who actually presented with flexion intolerance with back pain, and it was extension based corrections that helped them get out of pain. Although more on the uncommon side, anterior spine problems and flexion issues do exist in gymnastics. High force or improper landings with poor position into flexion may create this type of problem. Both for movement of the spine and detection of pain this is important thing to consider for gymnasts. This clearing test is the picture on right below

A gymnast should have the capability to fully flex their lower back without painor limitations. I’ve found it very common to see gymnasts who live in extension chronically show poor breathing patterns, and lose unweighted spine flexion. Living in constant lumbar extension puts stress on certain aspects of the spine as well as may set someone up for fulcrum based dynamic microinstabiltiy of the hip in extremes range of motion. Also, I have had 2 gymnastics patients who actually presented with flexion intolerance with back pain, and it was extension based corrections that helped them get out of pain. Although more on the uncommon side, anterior spine problems and flexion issues do exist in gymnastics. High force or improper landings with poor position into flexion may create this type of problem. Both for movement of the spine and detection of pain this is important thing to consider for gymnasts. This clearing test is the picture on right below

General Thoughts

- I also like the FMS because as I hinted the gymnast shows their “go to” pattern free of specific movement cueing. I think in gymnastics coaches sometimes cue and vocalize a ton for skill work, rather than just stay quite and see what the gymnast naturally does. Subconscious automaticmovement patterning is ultimately the goal. Also, it’s a deduction for a coach to talk in their routine so so there’s that too.

-

It’s not all-encompassing for the sport, and

I think the people who inventedthe test would be the first to tell you it’s not meant to be. It’s just a tool. Along with the FMS I think there are gymnastics specific patterns I like to always look at like a handstand, a bridge or back walk over, and a hanging tap swing or giant. I also look at some more dynamic testing like single leg and double leg squatting/jumping/landing, and whatever else I feel that gymnast needs. Then the role of fatigue and stress, but again that’s not what the FMS is meant for. I think in conjunction with the FMS a coach and gymnastics gym can come up with a great screening system that can go a long way for both health and performance.

I think the people who inventedthe test would be the first to tell you it’s not meant to be. It’s just a tool. Along with the FMS I think there are gymnastics specific patterns I like to always look at like a handstand, a bridge or back walk over, and a hanging tap swing or giant. I also look at some more dynamic testing like single leg and double leg squatting/jumping/landing, and whatever else I feel that gymnast needs. Then the role of fatigue and stress, but again that’s not what the FMS is meant for. I think in conjunction with the FMS a coach and gymnastics gym can come up with a great screening system that can go a long way for both health and performance.

- There are lots of correctives that can be given to the gymnast for pre-hab or prior to practice that can help out. Sometimes changes are faster than you think and keeping them isn’t so hard either. There are tons of corrections outside of the FMS that can be used. If it works, it works.

- I think this can be really helpful to keep tabs and baselines on the gymnasts as they develop, grow, move through competitive levels, and recalibrate to their system. Movement and the screen changes yearly, monthly, daily, and hourly depending on what you’re doing. If you throw an injury into the mix for a young gymnast that’s even more significant. Dr. Greg Rose had a fantastic lecture on screening youth athletes that if people are FMS members they should definitely check out. Especially when it comes to the topic of chronological age versus developmental age, and early vs late blooming athletes.

References

- Cook G. Movement: Functional Movement Systems: Screening, Assessment, and Corrective Strategies. Aptos, CA: On TARGET Publications, 2010.

- Schneides, et al. Functional Movement Screen Normative Values In Young, Active Population. IJSPT 2011 6(2)

- Cook G., Burton L., Hoogenboom B., Voight M. Functional Movement Screening: The Use of Fundamental Movements As An Assessment of Function Part 1. IJSPT June 2014 9(3)

- Cook G., Burton L., Hoogenboom B., Voight M. Functional Movement Screening: The Use of Fundamental Movements As An Assessment of Function Part 1. IJSPT August 2014 9(3)

- Weingroff, C. – 2015 Sports Rehab Expert Teleseminar/Video Addition Inservice – http://www.sportsrehabexpert.com/public/994.cfm

- Gray Cook, Lee Burton, Alwyn Cosgrove – The Future of Exercise Program Design

- Weingroff, C – Lateralizations and Regressions DVD. 2014

- Gray Cook, Craig Leibenson, Stuart McGill: Assessing Movement: A Contrast In Approaches & Future Directions

- Gray Cook, Dan John, Lee Burton. Essentials of Coaching and Training Functional Continuums DVD. 2014

- Gray Cook, Lee Burton. Key Functional Exercises You Should Know DVD.

- Leibinson, C. The Functional Training Handbook. Wolters Kluwer Health 2014

- Rose G. Why Screen Kids? 2014 (Video Lecture Recorded from Functional Movement Summit)

Related Resources

-

NBA Pre-Draft Assessments and the FMS

Posted by FMS

-

Movement Principle # 9

Posted by Gray Cook

Please login to leave a comment

2 Comments

-

Aram Bebekyan 8/12/2016 1:41:21 PM

Hi,

I'm a Certified FMS specialist level 1 and I got to say this article and you motivate me to go through school and become one of the top dogs like you guys. -

James Fitzerald 9/2/2016 1:57:24 PM

Dave, thx for your time in getting this data 1st and sharing it 2nd! i am Not a gymnastic coach but work with numerous athlete who have pre-requisite absolute strength and motor control for the shoulder but have small differences (as you put it 1/3 variance) in R to L scratch. Now, my observations have been that is there a possible subset of testing besides rotary control one can do to assess the closet chain association with "hanging" that is i believe missed in FMS in sport specific settings requiring forces though the shoulder with the hands being closed on bar as an example? i have not seen massive issues with upper pulling and straight arm hold and dynamic contractions with the variance - but DO see issues with it when we overload OHS, snatching, etc...from ground based forces...i am interested in your thoughts on this? we currently use single arm holds on ground, single arm db tests for R to L as well as hanging and upper arm flexion tests to compare against the scratch