Movement Principle # 2

Posted by Gray Cook

“Struggle is nature’s way of strengthening it.”

- John Locke

As individuals, fitness professionals and clinicians we tend to hate to struggle. Feeling like you are “not good at something” or that you “just aren’t getting it” can be frustrating. If you look around at how most folks organize their fitness (and maybe their lives) you will notice a lot of people training their strengths not targeting their weaknesses.

It feels good to do what we are good at but strengthening a link of the chain that is already strong will not improve the chain. Improving the chain comes from identifying the “weak link” and improving “that.” Just like movement screening helps you identify your movement weak link.

In the book Make It Stick the authors discuss the current perspectives and research on learning.

Wait… you were talking about strengthening chains a minute ago… and now “learning.”

Keep reading.

Whether academic learning or motor learning there are lessons to be learned about learning.

Think for just a moment about how you were taught to learn.

Practice – right? Lots of practice. Perform the “skill” you are trying to learn over and over and over. Read and reread and highlight and take notes on something for school. This sort of “rote” learning dominated the learning landscape.

Problem is that it isn’t the best way to learn. That’s right, all the hours spent going over and over and over a skill or poem you were trying to memorize was not the best way to go about it.

The key to learning is struggle. Being quizzed or tested and having that struggle for recall or performance (of a skill) is the key not “being correct.” Reread that if you want because yes I just said that being correct was not the key but the struggle for recall/performance was the key.

Rote practice feels good at the moment and has good results within a session, but it turns out it is stored in a more superficial way in the brain and does not lead to good results between sessions. (ie…it doesn’t “stick”) So what does and how do we apply it to movement screening and improving movement?

First a story… (I hear you groaning out there)

In the book (Chapter 3 of Make It Stick) they talk about a study done with young kids. The goal was to throw bean bags into a bucket three-feet away. After testing all the kids, they were divided into two groups. One group practiced throwing bean bags into a bucket the goal distance of three-feet away. The other group practiced throwing bean bags into buckets two and four feet away but never three.

At the testing at the end of the study the second group that never practiced the goal distance outperformed the group that only practiced the goal distance.

How?

Varied practice.

The varied practice in the study with the bean bags was the different distances used by the group throwing to the two and four-foot distances.

Pavel of StrongFirst told be some time ago that Russian shot-putters would throw to specific distances in their practice. 12 feet then 20 feet then 10 feet and so on varying the distance within a practice. (Honestly, I have no idea how far shotputters put shots but you get the idea) There is a deeper form of learning in the varied practice. Mixing the resistance between sets of an exercise is a form of varied practice. For the Get-up for example you might perform one set on each side for 5 sets but mix the weights so that set one = 24 kg, set two = 12 kg, set three = 32 kg, set four = 16 kg, set five = 24 kg. Or changing the resistance in FMT Chops from light to heavy to medium over three sets.

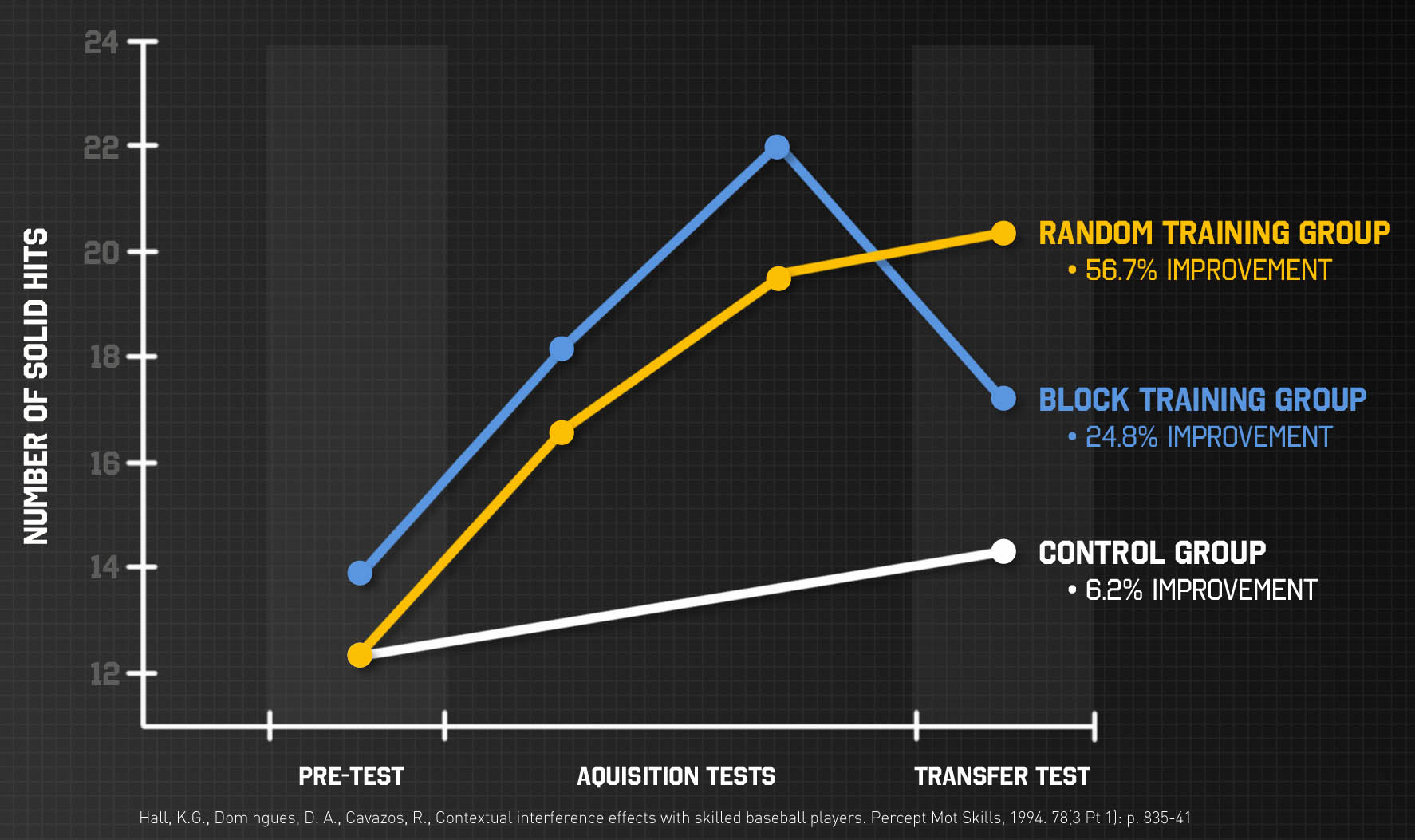

We can enhance the improvement of movement more by also incorporating what is referred to in motor learning as random practice. Block learning being the more “rote” method of repeating the same skill (like the kids throwing only the goal distance in the study). Random being just what the name implies and interleaving different skills and mixing the order in which they are performed. The research on Random vs. Block practice is strong for supporting the use of random practice. Numerous studies have reported a higher skill transfer after Random practice, even though the Blocked group performed better in practice. For example, a 1994 study of baseball batters tested improvement in hitting after 12 extra practice sessions. The Blocked and Random group faced 45 pitches: 15 fastballs, 15 curveballs and 15 change-ups. The Blocked group saw all 15 of each pitch in a row while the Random group were randomly presented pitches. During the six weeks of practice, the Blocked group actually out-performed the Random group DURING practice, but the Random group performed at a significantly higher level in the transfer test.

Let’s say you are working on improving an ASLR and have found that core engagement leg raise (CELR), half kneeling chop (HKC) and single leg DL (SLDL) improve the ASLR for your client. You may start by doing three sets of CELR followed by three sets of HKC followed by three sets of SLDL (block practice of each skill) because this allows your client to learn the drills in isolation.

Or you could perform what is referred to as Serial practice where one set of each exercise in sequence is performed for one to three tri-sets: {CELR, HKC, SLDL) x 3. To interleave the practice and really get random you mix the drills. The first tri-set might be CELR>HKC>SLDL. Second sets HKC>SLDL>CELR. Third set SLDL>HKC>CELR and so on. Creating a random practice of the three drills.

Or if you want to get crazy: Get-up left and right followed by CELR, Get-up left and right followed by HKC, Get-up left and right followed by SLDL.

You get the idea.

It turns out that varied and interleaved practice like this has better between session learning since it seems to stored in a deeper manner in the brain.

Use the FMS to target the weak link and use varied and interleaved/random practice to efficiently improve movement. Embrace the struggle!

Then continue to use these techniques to enhance learning of the skills and drills your client is learning.

Brett Jones, Chief SFG, is a Certified Athletic Trainer and Strength and Conditioning Specialist based in Pittsburgh, PA. Mr. Jones holds a Bachelor of Science in Sports Medicine from High Point University, a Master of Science in Rehabilitative Sciences from Clarion University of Pennsylvania, and is a Certified Strength & Conditioning Specialist (CSCS) from the National Strength and Conditioning Association (NSCA).

Brett Jones, Chief SFG, is a Certified Athletic Trainer and Strength and Conditioning Specialist based in Pittsburgh, PA. Mr. Jones holds a Bachelor of Science in Sports Medicine from High Point University, a Master of Science in Rehabilitative Sciences from Clarion University of Pennsylvania, and is a Certified Strength & Conditioning Specialist (CSCS) from the National Strength and Conditioning Association (NSCA).

With over twenty years of experience, Brett has been sought out to consult with professional teams and athletes, as well as present throughout the United States and internationally.

As an athletic trainer who has transitioned into the fitness industry, Brett has taught kettlebell techniques and principles since 2003. He has taught for Functional Movement Systems (FMS) since 2006 and has created multiple DVDs and manuals with world-renowned physical therapist Gray Cook, including the widely-praised “Secrets of…” series.

Brett continues to evolve his approach to training and teaching and is passionate about improving the quality of education for the fitness industry.

He is available for consultations and distance coaching by e-mailing him at appliedstrength@gmail.com.

Posted by Gray Cook

Posted by Jeffrey Tucker

Thanks Brett - very interesting! I'll try this with my clients.